Any tourist wandering through the glitzy lobby of Singapore’s Shangri-La Hotel this weekend would have stumbled on a rather bizarre scene.

Military officers from around the world thronged the halls of the luxury hotel, their shoulders dripping with gold braids and epaulets, complicated colored bars lined up on the chests of their dress uniforms like some martial game of Tetris.

Every few minutes a defense minister strode purposely through the mix, surrounded by a phalanx of aides and escorts.

This gathering is an annual spectacle that to the uninitiated might seem surreal. But the topics being discussed here are deadly serious.

The annual Shangri-La Dialogue is one of the few places in the world where you can watch warriors who spend their careers preparing for armed conflict, engaged in polite, carefully-moderated debate.

The stakes this year could hardly be higher.

War rages in both the Middle East and Europe. Meanwhile China’s increasingly assertive moves has much of the Asia-Pacific on edge.

The Singapore summit brought key players together.

Where else would you have the President of the Philippines, a nation whichdo has seen its vessels increasingly targeted by Chinese coast guard ships in the disputed South China Sea, deliver a keynote address on the same stage that, two days later, Beijing’s new Defense Minister makes his debut appearance?

There was even a surprise appearance from Ukraine’s embattled president Volodymyr Zelensky – and a first face-to-face meeting between US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and his Chinese counterpart Adm Dong Jun.

Given its location in the city-state of Singapore, events in Asia – and in particular China’s behavior in the region – stalked the conference.

In his keynote speech, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. issued a stark warning about the ongoing confrontations between Philippine and China Coast Guard vessels in a contested part of the South China Sea.

“If a Filipino citizen is killed by a willful act,” he said, “that is I think, very, very close to what we define as an act of war.”

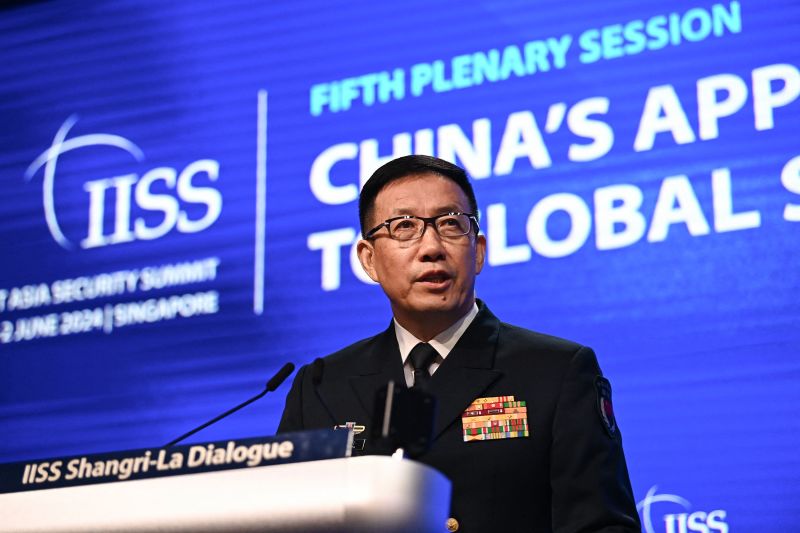

Two days later, China’s Adm Dong fired back from the same stage, accusing the Philippines of “blackmail” in the maritime dispute.

“There is a limit to our restraint,” said Admiral Dong Jun.

“I saw that as a threat,” said Dewi Fortuna Anwar, a research professor at Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Center who has been attending the Shangri-La Dialogue since its founding twenty-one years ago.

“In decades past, the Chinese only came in a small number and they were extremely quiet,” she said. “Now they’re very self confident…they intervene in all the sessions.”

The open nature of the Shangri-La Dialogue provides delegates with a unique opportunity to ask blunt questions of speakers.

After his speech on Sunday, China’s Dong received many questions from audience members on Beijing’s increased threats towards self-governing Taiwan as well as its disputed claims in the South China Sea, and he replied in unapologetic terms.

The “separatists” in Taiwan’s newly-elected government would be “nailed to the pillar of shame in history,” he said.

But equally, Chinese military officers also used Q&A sessions at other key moments to make their views known.

Senior Colonel Yanzhong Cao of China’s People’s Liberation Army asked US Secretary of Defense asked US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin whether the US was trying to build a NATO-like alliance in the Asia-Pacific region, adding the claim “the eastward expansion of NATO has led to the Ukraine crisis.”

“I respectfully disagree,” Austin replied, the audience in the ballroom then erupting into a rare burst of applause.

“The Ukraine crisis obviously was caused because Mr. Putin made a decision to unlawfully invade his neighbor,” Austin continued. “This was brought on because of a decision by Mr. Putin.”

Later that day, Ukrainian leader Zelensky got a borderline rock star welcome when he made a surprise appearance at the conference, dressed in his trademark fatigues and black t-shirt.

“We stand with you,” Ng Eng Hen, Singapore’s minister of defense, later said to Zelensky.

But the large contingent of Chinese army officers present at other sessions was notably absent during Zelensky’s speech and the Ukrainian leader said he failed to secure a one-on-one meeting with Chinese officials during his Singapore visit.

He also accused Beijing of aiding Ukraine’s mortal enemy.

“With China’s support to Russia, the war will last longer. That is bad for the whole world, and the policy of China – who declares that it supports territorial integrity and sovereignty and declares it officially. For them it is not good,” Zelensky told journalists.

It was not clear whether Zelensky succeeded in securing new support for Kyiv from non-aligned south-east Asian countries like Malaysia and Indonesia.

Instead, Indonesian president-elect and retired general Prabowo Subianto – the new leader of the world’s most populous Muslim majority nation – spent much of his speech calling for an end to the on-going carnage in Gaza and an investigation into recent Israeli attacks that killed dozens of displaced civilians in Rafah.

Another political elephant in the room was what direction might the United States be heading in.

The Singapore gathering began just hours after a 12-person jury in a court-room in New York City convicted former US President Donald Trump on of all 34 counts of falsifying business records in his hush money criminal trial.

Asia is watching very closely for whether Trump will return to office in November and what impact that might have on the world’s most populous continent and a region already fraught with very real geopolitical fault lines.

His fellow Republican Senator Dan Sullivan also requested not to discuss Trump during a meeting with journalists, instead directing reporters to a press release.

“This is a very sad day for American and the rule of law,” Sullivan’s statement said, calling the verdict a “gross abuse of our justice system.”

But speaking to journalists, the Senator from Alaska also celebrated what he called America’s “commitment to liberty and democracy,” saying this marked a competitive advantage over “authoritarian aggression led by China, Russia, Iran and North Korea.”

Sullivan was part of a bi-partisan delegation seeking to demonstrate Congressional commitment to US allies in Asia.

“The dictators we are allied against…are ally poor,” Sullivan said.

But there are clearly concerns about US reliability.

An academic from Japan – Washington’s closest ally in Asia – asked defense chiefs from Singapore and Malaysia about Trump’s possible re-election. He called it a “nightmare” scenario.

That triggered nervous laughter from the audience and on stage.

Singapore’s Dr. Ng Eng Hen gamely responded, “we will work with any administration in any country if we can find common ground.”

I vividly remember collective nervousness at the 2017 Shangri-La Dialogue, held just months after Trump’s inauguration.

Trump’s then secretary of defense James Mattis clearly sought to reassure American defense partners worried about the new mercurial president.

“Bear with us,” Mattis told the audience, after being asked whether the “America First” commander-in-chief would contribute to the destruction of the post-World War II order.

“Once we’ve exhausted all possible alternatives, the Americans will do the right thing. We will still be there.”

Seven years later, uncertainty over the political future of the US is just one of many challenges facing policy makers.

One by one, the leaders of armies and navies shared their fears about climate change, nuclear proliferation, wars in Europe and the Middle East and concerns that a miscalculation between the US and Chinese militaries could spiral out of control

“The world cannot withstand a third geopolitical shock,” Singaporean defense chief Dr. Ng warned, after invoking the Gaza and Ukraine conflicts.

In this tense geopolitical environment, it’s far better for commanders to put on their dress uniforms and rub shoulders in the halls of a five-star hotel, than aim at each other over gun barrels on the battlefield.