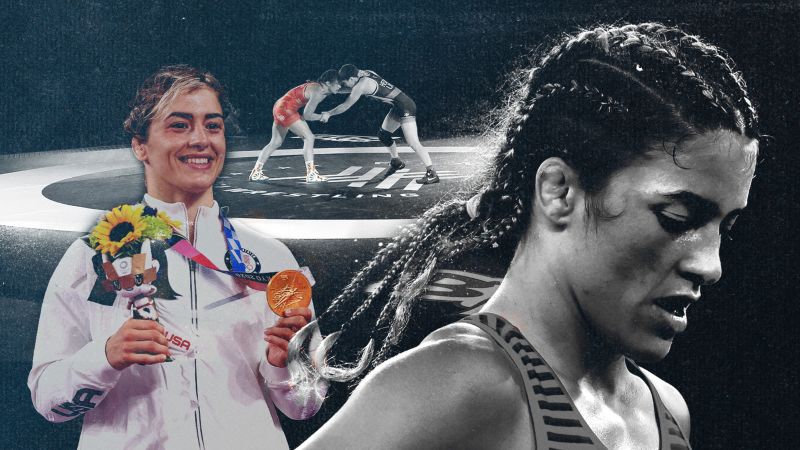

Three years after becoming the first American woman to win an Olympic gold in wrestling, Helen Maroulis was told she was about to be admitted to a psychiatric ward with suicidal thoughts.

“I was completely normal, and all of a sudden they put me in this psych ward.”

Maroulis’ journey both on and off the mat – and her struggle to get back to her beloved sport after overcoming debilitating concussions – has been an inspiration to many, not least Hollywood star Chris Pratt, who has recently produced a feature film charting the highs and lows of the 31-year-old’s decorated career.

Her first foray into the sport aged seven arrived almost by accident, subbing in as a partner for her younger brother because there weren’t enough kids on his team.

“My mom didn’t want to make him quit for that season, so she just told me to take my shoes off and jump in there. Be a dummy,” Maroulis says.

After two weeks of wrestling with the boys, she knew she wanted to compete – and not just as a “dummy.” So her father made a bet: if she wrestled and won one match, she could carry on with the sport.

“It was the only match I won all year; I call it fate,” Maroulis remembers.

By college, the Maryland native was a four-time WCWA (World Class Wrestling Association) national champion and went on to win age-group and senior world medals for Team USA. At the 2016 Rio Olympics, she became the first American woman to win gold in wrestling after defeating Japan’s Saori Yoshida, a 13-time world champion and a formidable opponent.

It’s a moment Maroulis describes as “surreal.”

“It was such a dream come true. It was this special moment where you get to go do what you love in front of thousands of people. You represent your country, and you leave your heart there on the mat,” she says.

But while training for the Tokyo Olympics in 2019, Maroulis’ dreams were derailed.

‘An invisible injury’

Over two years, between 2018 and 2019, Maroulis had three concussions which eventually pushed her from the top of her game and sent her spiraling.

A concussion is a brain injury which occurs after a hit to the head or body, causing the brain to move back and forth inside the skull, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Typical symptoms can include feeling dizzy or groggy, having a headache, feeling nauseated or vomiting, being bothered by light or noise, and experiencing concentration or memory problems.

Females may be more susceptible to concussion, and they have worse and more prolonged symptoms after their injury than men, according to a review of 25 studies of sport-related concussion published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, with “biomechanical differences and hormonal differences” listed as possible factors.

“I would literally have these personality changes, or these dizzy bouts or vertigo,” Maroulis says. “It was just really challenging to navigate all that.”

She says people would ask: “‘Did you get knocked out? Did you pass out? Did you throw up?’ I’m like, no, none of those things,” instead describing concussion as an “invisible injury.”

“It felt like there was a period of time when I just wasn’t really identified with anything, like I didn’t know who I was,” says Maroulis. “I just had such a struggle [with] being normal. It was way bigger than sport. It was just like: oh my gosh, I just … want to be normal again.”

Although each of her three concussions was diagnosed by a doctor, treating the symptoms proved more challenging.

Maroulis had struggled with anxiety and PTSD for a number of years – something she says she had started to manage prior to the concussions.

“Between 2012 and 2016, I did so much work on myself to overcome that. And I really felt like, oh, I don’t think I struggle with this anymore, and I was so proud of that. And then when I got the concussions, it felt like a lot of that flooded back,” she says.

“I remember feeling like I’m crazy, like I’m right on the edge of insanity.”

It was after one incident mid-match, a “freak accident” in 2019 in which she was slapped in the ear at practice, that Maroulis found herself in that psychiatric ward.

In the two years that followed, she says she tried to hide how she had been affected by the head injuries.

“As an athlete, you don’t want to show any weakness,” Maroulis says.

“I knew that there was … a lot of expectation on me at this point in my career. So I just felt like I always wanted to just live up to the expectation more from pursuing a standard of excellence, but maybe also just from my whole life being a girl in the sport.”

But her struggles with anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder were bleeding into every part of her life, and she said she couldn’t even walk into the wrestling room without having panic attacks.

“My relationship with wrestling felt so damaged and broken,” she adds.

A long recovery

Eventually, Maroulis realized she was pushing herself to achieve at the expense of her own health.

“I realize that you are replaceable to everybody except yourself. And I’m like, I cannot do this to myself anymore. I can’t ask my body to go wrestle a match just to make these people happy,” she says.

She took half a year out to recover, returning in early February 2020 to wrestle in the Pan-American Olympic Qualifier tournament, and also undertook several treatments.

Besides an initial SCAT test and symptom monitoring, Maroulis underwent ocular and vestibular training and biofeedback therapy. She also used prism glasses for eye correction, used a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, and underwent neuropsychology and counseling.

A soft tissue manipulation known as Fascial Counterstrain (FCS) also proved to be very helpful, she says.

“I wanted to come back because I love [the sport] and I want to ask the most of myself and I want to heal my relationship with wrestling and enjoy this again like I did as a little kid,” says Maroulis.

When considering a comeback, she consulted medical specialists throughout, asking whether she was at higher risk of concussions.

Doctors concluded that she wasn’t and that the second concussion she’d had was unusual and not reflective of a wrestling match.

She ultimately got clearance to wrestle again from sports medical staff at the Olympic Training Center, her neuropsychologist, and her coaches, although she was monitored throughout her comeback.

“I’m one of the very lucky and blessed cases,” says Maroulis. “There are so many situations where I’m just in the right place at the right time, or I met someone that works on concussions outside of the network of help that they were providing, and that person was able to help me tremendously.”

More support needs to be given to young athletes experiencing concussion, Maroulis believes, particularly when some might delay seeking support for fear of seeming weak.

“I’ve had young athletes I’ve had to talk to about this. You have nothing to prove. Tell them how you actually feel and never lie about your symptoms. Pushing through because you don’t want them to think you’re weak is the worst thing you can do,” Maroulis says.

“I am a gold medalist, and I struggle with that. So I can’t imagine a high school kid – they’re just starting the path, chasing the dream. And they don’t want their coach to think they’re weak, or their parents or their teammates.”

Now, Maroulis is training for the 2024 Paris Olympics and the World Wrestling Championships in Belgrade, Serbia this September.

Her story caught the attention of lifelong wrestling fan Pratt, who believes that Maroulis’ resilience makes her “the very best in the world at what she does.”

“Helen | Believe” was produced by Religion of Sports, the venture founded by Gotham Chopra, Michael Strahan and Tom Brady.