European officials took some small comfort when China attended a summit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, last weekend. The meeting aimed to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Ukraine.

While Beijing didn’t budge from its stated position of impartiality, China’s mere presence at a meeting to which Russia says it was not invited has, some sources claim, sent a message to the international community that it’s not willing openly to pick Russia’s side against the West.

It might be a very small victory, but in the diplomatic world of zero-sum games, Russian President Vladimir Putin not getting exactly what he wants is something to celebrate.

“From our point of view, China is visibly engaging with the West, talking to the Ukrainians, and pushing back on Russia. We really welcome that,” the official said. Multiple European sources have echoed this view.

However, while China’s engagement with the international community might be a blow for Russia, it’s still being viewed with suspicion by Western allies, not least because of the continued economic, diplomatic and security ties the countries share.

Despite the optics of its delegation’s attendance in Jeddah, Beijing has not appeared to scale back ties with Russia. Its top diplomat, Wang Yi, called his Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov a day after the Jeddah talks concluded, reiterating Beijing’s “impartiality” in the conflict.

The two countries’ militaries have continued joint exercises throughout the war, including a naval patrol off the coast of Alaska last week. Putin is also expected to visit China in October, according to Russia media, after being invited by China’s Xi Jinping in March.

The same senior EU official acknowledged that there is little incentive in China for the war to stop outside of Beijing’s external relations with economic partners. “From their perspective, its biggest rival, the US, is distracted and Russia has become even more of a junior partner. The only downside is how it makes others think about China.”

It’s no secret that China’s relationship with Europe has become tetchy. That, officials say, is bad for Chinese leaders who see European nations as up for grabs in the battle for global dominance between Beijing and Washington.

It’s also no secret that China’s close ties with Russia – and failure to condemn Moscow’s full-scale invasion – have made a number of European countries, especially those geographically close to Russia, uncomfortable and led to a rethink in what Europe’s relationship with China should be.

Alicja Bachulska, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, agrees:

“China’s current activities are definitely about damage control in terms of PR. China is sitting on the fence and it will continue doing so until it can. Attending this kind of meeting, especially if Russia is not involved, fits very much into this strategy. It makes good headlines for all those who still believe, quite naively in my view, that China can make a difference.”

In short, China coming to the table hasn’t moved the dial in Brussels on what is arguably the EU’s most complicated but important international relationship.

Europe still imports vastly more from China than it exports, a reflection of the level of dependency it has on China. In 2022, the trade deficit was €396bn ($436 billion), more than double that of 2020.

However, this has happened against the backdrop of Europe cooling on signing official treaties and agreements. The Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, negotiated for nearly a decade before being agreed in principle, is on ice because China has sanctioned Members of the European Parliament for criticizing China’s human rights record.

Europe has also changed its official view of China, acknowledging in 2019 that Beijing is a “systemic rival.” Since 2019, Brussels has undertaken specific policy initiatives that deliberately aim to challenge China’s dominance in Eurasia.

The official explained that even positive steps like this are ultimately weighed against other behaviors, such as Beijing’s respect for human rights, its threatening stance toward Taiwan and alleged state-sponsored corporate espionage. In that respect, China’s action or inaction on Ukraine is just another lens through which Brussels can view its various gripes against Beijing.

This dual reality, Europe needing China for some things but deeming it a security risk and nefarious actor on the world stage, is what makes all this such a headache.

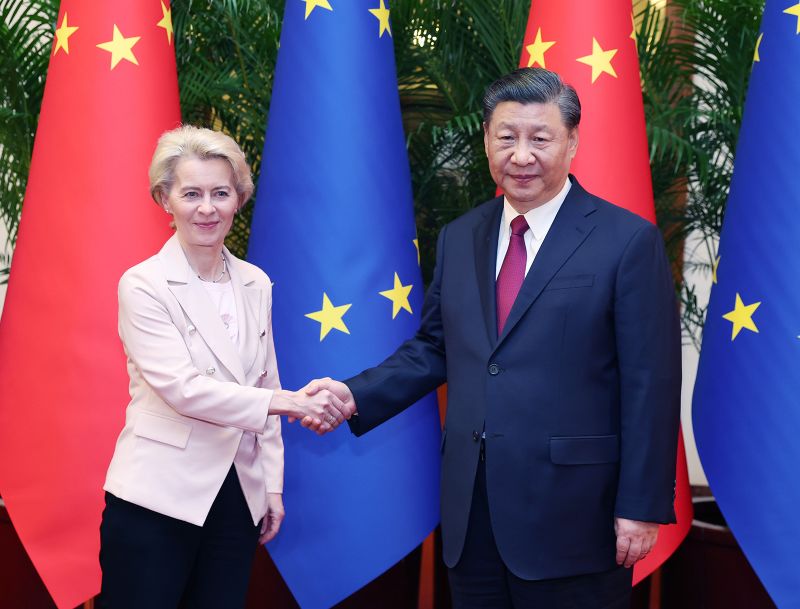

Indeed, even with relations as tricky as they are, China has welcomed the leaders of France, Germany, Spain and even the European Commission president herself, Ursula von der Leyen, in recent months.

Brussels has set itself ambitious objectives in areas like climate change, leading the way on new technologies and having an independent foreign policy. The EU didn’t want to pick between the two main powers of the East and West, so opted for a third way where the US remained its primary partner, but it would deepen economic ties to China.

In doing so, it hoped it could encourage China to fall in line with European thinking on climate change, the rules-based international order and human rights, among other things.

In 2023, European officials know that China represents a major security concern and that becoming overly dependent on China is a risk. But they also accept that if they’re to achieve their lofty aims, they might need China’s help.

“The big dependencies of the future will be things like cheap electric vehicles, solar panels, steel for wind farms. These are things that China can produce cheaply and already has a head-start in terms of becoming a major provider for the international market,” says Sam Goodman, from the China Strategic Risks Institute.

Goodman also notes that Europe’s current economic outlook could leave smaller states susceptible to the lure of Chinese money in terms of big infrastructure projects.

“China has historically been keen to buy up or heavily invest in European infrastructure projects, be they nuclear power stations, roads or water companies,” he said. “European nations have cooled on this lately, but it might be tempting for countries struggling economically to take some money as a quick-fix.”

Others say that Europe doesn’t want to end up in the same position it did with Russia in terms of relying on one provider so heavily for energy or other resources, especially in the event China becomes even more forceful in its own backyard and goes from systemic rival to full-blown international pariah, as seen with Putin’s Moscow.

Between these fears over security, Europe’s international ambitions and China’s global ambitions, it might seem hard to pin down exactly what either side want from their future relationship.

“I don’t think that China yet sees Europe as a lost cause. It hopes it can still turn the heads of enough European countries that it can stop America running away in the battle over new technology,” says Charles Parton, former first counsellor to the EU delegation in Beijing.

“They have lost on things like Huawei recently and will be desperate to remain competitive on semiconductors, AI, all the things that will matter a lot in the coming years,” he adds.

For Europe, it’s more complicated. Officials say Brussels is committed to walking the narrow path of the US remaining its closest ally while resisting Washington’s calls to completely disengage with China. It will achieve its global aims without becoming overly dependent on China, they say, while simultaneously working with China on some of the most important issues facing the world today.

It’s an ambitious approach, but one leaves much of its own future in the hands of fate. Or at the very least, in the hands of a country that has been downgraded as a partner to Europe so significantly in the past decade.